Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin’s collaboration is a shrill and harassing scream that echoes throughout the room. It is a sum of primordial and disturbing silhouettes imbued with morbid fascination. The product of Bourgeois’ mind combined with Emin’s is a series of sixteen dirty, macabre nudes. The woman is a womb, and the man is a phallus. The combination is repulsive and magnetic.

The two artists began collaborating in 2009 when Bourgeois handed her colleague a series of “male and female profile torsos on paper in red, blue and black gouache pigments mixed with water” (Davis 2011). Emin recalls their first meeting, in Bourgeois’ apartment, where she was “screaming, shouting, angry, and shaking her fist, […] I just remember thinking: this woman is free. But the irony was that even though this woman was being emotionally free, she was making reference to the emotional entrapment of her life.” (McNay 2011). It was difficult for Emin to get her hands on Bourgeois’ work. Fear of ruining her colleague’s work resulted in her completing it only two years later, adding “smaller, [stylized] fantasy figures and handwritten narration” (Davis 2011). At the end of 2010, Do Not Abandon Me was completed.

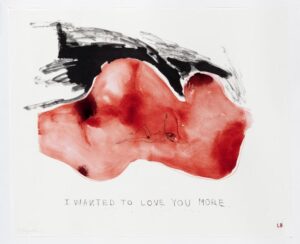

In the first of the sixteen, “I Wanted to Love You More,” we find a woman imprisoned in a womb as if to indicate the impossibility of breaking out of the done-and-finished role of mother and begetter. Red hues alternate with black; the feeling is of being on a crime scene.

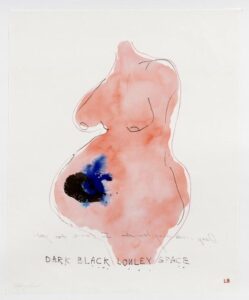

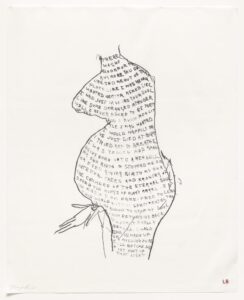

“Deep inside my heart” there’s a “dark black lonely space,” once filled by a foetus, now lost, aborted – number three of sixteen. The theme of abortion is central to the series; it occupies most space and draws directly from the personal experiences of the two artists. It is experienced and represented both as a voluntary decision and as an adverse event but, in both cases, it constitutes a loss. In the former, pregnancy is the loss of one’s body, of one’s freedom; in the latter, it is the loss of life, of motherhood, of choice. Examples of the latter are “Looking for the mother” (number six), “I lost you” (number nine), “Reaching for you” (number thirteen) and “Waiting for you” (number fifteen).

In “I Just Died at Birth,” number eight, the unborn child comes to life, and it has a voice: “There was no room for me anymore. You squeezed me out of that place like I was never wanted, never asked. Like I had just invaded your soul, like some deranged intruder. Well, I never asked to be part of you. Now I know how little I was wanted. I would happily have just died at birth. I tried not to breathe. I was yellow and small being born into a new hell. My own birth stopped me from ever giving birth.” We see it on the outside, anchored to the woman, spilling out from where the vagina is anatomically positioned.

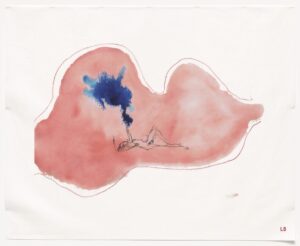

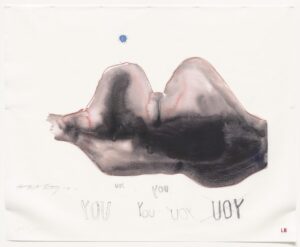

In the canvases, sexual appetite is unleashed in the encounter with the opposite sex. Although male bodies occupy the central place in the economy of the drawing, women are the leading players. It is a cold and, in most cases, violent and abusive encounter.

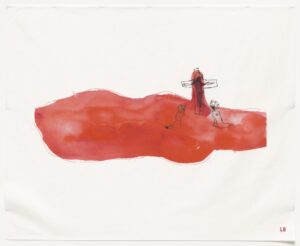

In “Come unto Me,” number five of sixteen, the penis acts as a support for a cross, where a woman is being crucified. Below her we see other female figures kneeling, pleading, and praying. Torture is taking place and we are spectators.

The crime finds completion in number seven, “I held your sperm and cried,” where a blue phallus rises above a kneeling woman and the pleasure reaches its peak, of the man of course.

In “Just Hanging,” a woman hangs from a noose that hangs from a dick, the killing weapon. The latter is marked and highlighted in all the paintings, with darker colours, immediately capturing the audience’s attention.

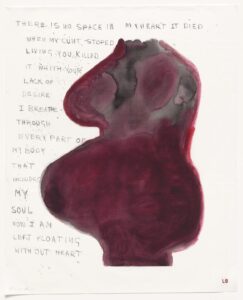

The collection ends the moment the pussy ceases to be when the woman dies. “There is no space in my heart. It died when my cunt stopped living. You killed it with your lack of desire. I breathe through every part of my body including my soul. Now I am left floating without heart.” The female torso remains, this time alone, without foetuses or phalluses.

Sources

Davis L. 2011. Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin, Do Not Abandon Me. AnOther magazine. https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/829/louise-bourgeois-and-tracey-emin-do-not-abandon-me.

McNay A. 2011. Louise Bourgeois, Tracey Emin: Do Not Abandon Me. Studio International. https://www.studiointernational.com/louise-bourgeois-tracey-emin-do-not-abandon-me.