Prostitution “is officially acknowledged as a form of exploitation of women and children and constitutes a significant social problem, which is harmful not only to the individual prostituted person but also to society at large” (McCarthy et all, 2012; Honeyball, 2014).

Prostitution involves almost 42 million people worldwide. Since most of the sellers are women and young girls, it is considered a gendered phenomenon that participates in the production of gender inequality: it has an impact on the status of women and on the relationships between men and women, hence it is both a cause and a consequence of the social disparity between them (Honeyball, 2014). The European Parliament considers sex work a “form of slavery incompatible with human dignity” and a violation of fundamental human rights as it reduces human beings into objects, mere merchandise that can be bought, sold, replaced, and thrown away (ibid).

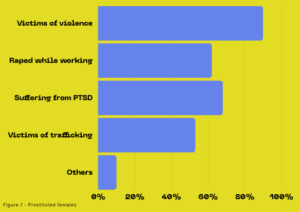

The vast majority of the prostituted persons come from disadvantaged and vulnerable groups: 80-95% of them have suffered some form of violence before entering prostitution (rape, incest, paedophilia), 62% of them report having been raped and 68% suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (Farley et all, 1998). Moreover, according to the 2020 report of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, more than 22 million are victims of trafficking for sexual purposes – more than 53% of the sex workers (UNODC, 2020).

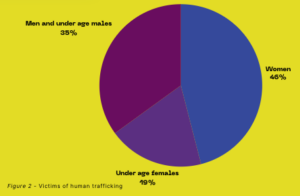

The true number of victims is unknown for two reasons: first, human trafficking is a clandestine activity; second, trafficked persons are part of the ‘hidden population’ (McCarthy, 2014). Of the 49 million detected victims of trafficking reported, 46% are women and 19% are under-age females (UNODC, 2020). Of them, more than 70% (almost 32 million females) are trafficked for sexual exploitation (ibid).

Usually, traffickers take advantage of pre-existing factors like economic need (51%), children with a dysfunctional family (20%), intimate partners as traffickers (13%), etc. (ibid). For this reason, policies and “strategies to prevent trafficking in persons need to target marginalized communities”, reinforcing social ties and safety nets, and addressing economic, social and cultural inequalities (ibid). “The establishment of specialized agencies dedicated to preventing and combating trafficking in persons, as well as to assisting victims, can facilitate” international dialogue promoting coordinated and more efficient responses (ibid).

In terms of illegality, prostitution is not only connected to human trafficking but also to drugs, violence and murder (Bindel et all, 2003). According to Bindel and Kelly’s report on the condition of prostitutes in several cities in the UK, a high percentage of sex workers claim to have been involved in prostitution to finance their addiction to drugs (ibid). Most prostitutes have also been victims of at least one episode of physical violence, particularly those working on the streets (ibid). Assaults are generally perpetrated by clients, pimps, boyfriends and, for street prostitutes, by passers-by and residents (ibid). Most of these abuses are not reported to the police, and this reluctance may be one of the factors behind the high mortality rate among saleswomen in the sector (ibid).

Prostitution policies not only affect the lives of those involved in the industry (sellers, pawns, customers) but also prevent and counteract the illegal practices mentioned above. Three policy regimes can be adopted: full criminalisation, partial decriminalisation and full decriminalisation.

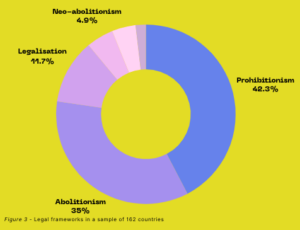

Full criminalisation consists of the ban on sexual services (McCarthy et all, 2012). Two legal approaches are the most widespread: prohibitionism and neo-abolitionism.

The first model is commonly spread in most religious states, here the whole landscape of paid sex is illegal: selling it, buying it, organising it and soliciting it (World Population Review, 2022). In 2022 69 states followed this model, two of which have a mixed legal approach that varies by state or territory (El-Salvador and the United States) (ibid).

Neo-abolitionism, on the other hand, considers prostitution to be violence against women, therefore it is not the selling of sex that is against the law, but the buying, organising and soliciting of it (ibid). This legal framework is designed to suppress demand and has been adopted by Belize, Canada, France, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Norway and Sweden (ibid).

Partial decriminalisation “assumes that the nature of sex work depends on its context […], selling [is therefore allowed] in some situations but prohibited in others” (McCarthy et all, 2012). This approach tries to manage sex work rather than abolish it.

The most common model is abolitionism, widespread in 57 states where soliciting, procuring and forcing prostitution are considered illegal in an attempt to prevent the exploitation of sex workers (World Population Review, 2022). There are minor cases of mixed legal arrangements and states where “prostitution is prohibited but many loopholes exist” (e.g. Italy) (ibid).

Full decriminalisation is present in 22 states, where prostitution is legal at all levels (McCarthy et all, 2012).

The most diffused model is legalisation, which is present in 19 states. In these states, selling, buying, and some forms of soliciting and organising are legal but regulated (World Population Review, 2022).

Decriminalisation is present in Cape Verde and Indonesia, differing from the above only in that regularisation is minimal or absent (ibid). An exception is Australia, where prohibition and legalisation alternate in various areas (ibid).

All these policy regimes consider human trafficking an illegal activity, however, anti-trafficking policies are weak, particularly when it comes to protecting victims.

Cho, Dreher and Neumayer developed an index to measure the effectiveness of 180 countries’ policies on human trafficking between 2000-2010. The research considers three dimensions that characterise these policies: the prosecution of traffickers, the

protection of victims and the prevention of the crime of human trafficking (Cho et all, 2014). They found that anti-trafficking policies decrease with corruption and are higher in countries that respect women’s rights or have a higher percentage of women in the government (ibid).

Regarding the problem of addiction among sex sellers, studies indicate that to curb it, it would be necessary to work on programmes that incentivise a change in the lives of these people, that give them a sense of meaning, and prospects, such as changing their living conditions, getting them into detoxification programmes, and even getting them out of prostitution (Bindel et all, 2003). Policies, therefore, should not be oriented towards repression, but towards rehabilitation.

Policies on prostitution not only have an impact on prostituted persons but also, as the European Parliament points out, on achieving gender equality, affecting the understanding of gender issues and delivering messages and norms to society, including its youth. Beyond prostitution laws, much should also be done to offer alternatives to prostitution. It would be important for future researchers to delve into this issue, perhaps starting with the reasons why people prostitute themselves and looking for solutions to problems such as poverty and drug addiction, it would be interesting to conduct qualitative research that confirms the data collected by Farley, Baral, Kiremire and Sezgin on the incidence of a history of violence among sex workers.

Sources

Bindel J., Kelly L. (2003), A Critical Examination of Responses to Prostitution in Four Countries: Victoria, Australia; Ireland; the Netherlands; and Sweden.

Chang G., Kim K. (2007), Reconceptualizing approaches to human trafficking: new directions and perspectives from the field(s), Stanford Journal of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

Cho S., Dreher A., Neumayer E. (2014), Determinants of Anti-Trafficking Policies: Evidence from a New Index, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43673673.

Farley M., Baral I., Kiremire M., Sezgin U. (1998), Prostitution in Five Countries: Violence and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.522.9029&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Honeyball M. (2014), Report on sexual exploitation and prostitution and its impact on gender equality, Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-7-2014-0071_EN.html.

McCarthy B., Benoit C., Jansson M., Kolar K. (2012), Regulating Sex Work: Heterogeneity in Legal Strategies, Annual Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102811-173915.

McCarthy L. A. (2014), Human Trafficking and the New Slavery, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110413-030952.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2020), Global report on trafficking in persons 2020, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tip/2021/GLOTiP_2020_15jan_web.pdf.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2020), Prevalence of Drug Use in the General Population, https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-drug-use-prevalence.

World Population Review (2022), Countries Where Prostitution Is Legal 2022, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-where-prostitution-is-legal.

World Population Review (2022), Poverty Rate by Country 2022, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/poverty-rate-by-country.

Further readings

International Organisation for Migration, Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative,

https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/.

Joint United Programme on HIV and AIDS (2020), Sex Workers: Size Estimates,