For the pseudo-Kantian optimists who see humanity’s intent in a process toward the better, here is a statistic that you too will find alarming: gender equality is 132 years away.

In 2154 women will flock into parliaments, fill heads of state summits, lead most of the more profitable companies, lead immense multinational corporations, and be spiritual leaders, popes, and Imams, and we will witness all of this. Ah no, we would be dead. All dead: us, the newly born, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

According to the Global Gender Report of this year, the global gender gap is currently 31.9 %, where political power and economic participation are the most worrisome data, as well as the most difficult to overcome. Women are mostly absent in leadership positions, and their reduced social influence disadvantages them both in terms of economic power and political representation – the factors that most determine empowerment (Larsen et al. 2021, World Economic Forum 2022). As empirical analyses show, these are exacerbated by the various crises that have erupted in recent years: the 2008 Great Global Recession and the subsequent decade of austerity, the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, this year’s energy crisis, geopolitical conflicts, and climate change (World Economic Forum 2022).

Crises always disproportionately affect those strata of the population that are already in an underprivileged condition. In the first place, economic recession impacts the primary form of aggregation – the family – changing first and foremost the fate of the “housekeepers.” Consider the results of the last pandemic: primary caregivers gave up their careers or reduced working hours because they had to stay home with their children or care for sick relatives (ibid). Moreover, when personnel cuts occur, women are the first to pack their belongings.

When explaining workforce gaps, several aspects need to be considered: long-standing structural barriers, socioeconomic and technological transformations, societal expectations, employer policies, glass ceilings, the division of household labour and availability of care, the legal environment, and, finally, educational paths and career trajectories (Verashchagina et al., 2009; World Economic Forum, 2022).

According to the Global Gender Gap Index, the highest performing states regarding gender equality are Iceland, Finland, Norway, New Zealand and Sweden (World Economic Forum 2022). The Index offers a global account that tracks the current state and evolution of gender equality in 146 countries by considering four dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, political empowerment, educational attainment, and health and survival (ibid). The last two sub-indices score the highest; as mentioned earlier, the disparity is most pronounced in the political and economic sectors.

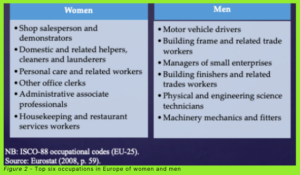

The statistics show that the Nordic countries – excluding Denmark – confirm themselves as the paradise of gender equality but, as researchers Larsen, Moss and Skjelsbæk point out, high levels of horizontal and vertical segregation exist even in the so-called “gender paradises.” Women and men hold different professions, and the highest positions are the domain of men (Larsen et al. 2021). This reflects global data, where occupational and sectoral segregation has not changed significantly since the early millennium; indeed, this year parity in the labour force is the lowest recorded since 2006 (Verashchagina et al. 2009, World Economic Forum 2022).

Of these, Sweden is the state with the highest level of parity in the economic field, ranking fifth. Here, as in Iceland, New Zealand and Norway, women’s participation in the labour sector is very high, including in professional and technical roles (World Economic Forum 2022). The high female presence is supported by paid parental leave: in Norway, there is 100% coverage for 49 weeks or 80% for 59 weeks, as well as paid leave for nursing mothers and a cash subsidy for assistance when children do not attend state-sponsored daycare (Larsen et al. 2021). In these countries, segregation is felt most at the vertical level, where men are predominantly in senior and managerial positions. The only state where parity at the top has increased is Finland, where, however, women in the workforce have declined, as have their wages – Iceland and Sweden are the only ones with parity in labour income (World Economic Forum 2022).

“Nordic countries play the role of moral superpower in global hierarchies”; however, gender equality policies are more a manoeuvre of national branding and de jure legal rights than de facto (Inglehart et al. 2003, Larsen et al. 2021, Teigen et al. 2009). For example, in Norway’s gender equality legislation – which prohibits direct and indirect discrimination and establishes proactive obligations for state agencies and public and private employers – there is a general avoidance of specificity and limited implementation and enforcement (Larsen et al. 2021). Only a few discrimination cases have been brought to court, which means that equality laws are mostly symbolic legal statements, and thus have limited real consequences (ibid). Another controversial case is related to the parental benefit scheme. The father’s right to parental leave depends entirely on whether the mother works, a law that blatantly violates the European Union’s Equality Directive since it does not apply in reverse (ibid).

What most affects career opportunities and advancement is the unequal division of housework, fomented by inherent societal biases. Dealing with “caregiving” means less time, less autonomy, more emotional and mental burden, less job stability, more shift work, and lower pay. Policies and infrastructures such as those carried out by Norway, which provide caregiving assistance, need to be implemented and adopted by other countries.

The Nordic model is not exhaustive, but it is in fact a model: the state must take responsibility, and take care of its members. The practice of using free labour in care must be eradicated through policies that actually produce egalitarianism.

Sources

Inglehart, Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/30721516/RisingTide-with-cover-page-v2.pdf?Expires=1669222916&Signature=fKg6KqRnkfs4wRGaah~G9uK-cDH2etkoWRZ0Sj7fRO4V71oU2ZhHmTttsfXvacGOa-PHzuy1U4cghuP6nVT4E9T~3iE43V1QWk~zzVl5rG0FjhuYUj2C~Dl4mBsTK7WmNCQxYvzRBG2qVPu4K27r1Ntl~j9Qzr~~Dhk01YKQgO2LLlqUc19qXYe6LpfAROekMna21dlLLsMmbZXSJ2qD8AbeX5gbEtXPzcSmM5jUTE7JPz1ZxEDBY3YqokywtOa~g2eCJHjEGx68wK8160FyFB9h~Rmxgt30iK37qqkBXSNgDaZcL3xug9Dd-qil~gTUj-IlthavnOHoDEeQBpCatQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

Larsen, Moss, Skjelsbæk. 2021. Gender Equality and Nation Branding in the Nordic Region. Oxon, New York: Routledge. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/48771/9781000408188.pdf?sequence=1#page=30.

Teigen, Wängnerud. 2009. Tracing Gender Equality Cultures: Elite Perceptions of Gender Equality in Norway and Sweden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1743923X09000026.

Verashchagina, Bettio. 2009. Gender segregation in the labour market. Root causes, implications and policy responses in the EU. European Commission. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/39e67b83-852f-4f1e-b6a0-a8fbb599b256.

World Economic Forum. 2022. Global Gender Gap Report 2022. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf.